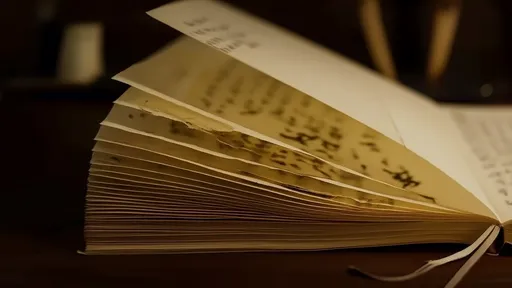

In the hushed chambers of conservation laboratories and the hallowed halls of rare manuscript collections, an ancient material breathes with quiet persistence. Xuan paper, the legendary Chinese writing surface that has carried imperial decrees, poetic masterpieces, and philosophical treatises for over fifteen centuries, reveals its most extraordinary secret not in its smooth surface or remarkable durability, but in its living relationship with the air itself.

The phenomenon scholars have come to call "The Dry Concerto" refers to the barely audible symphony of microscopic movements as Xuan paper fibers expand and contract with atmospheric changes. This isn't mere physical reaction - it's a dynamic conversation between human craftsmanship and elemental forces, perfected through generations of papermakers in China's Anhui province.

Modern conservation science has only recently developed instruments sensitive enough to measure what traditional artisans knew instinctively. The paper's fibers, derived from the bark of Pteroceltis tatarinowii trees and blended with rice straw, arrange themselves in a lattice so precise it responds to humidity changes like the wooden joints of ancient architecture. During dry periods, the fibers contract with such uniformity that conservators report hearing faint creaking sounds from ancient scrolls - not the distressing crackle of deterioration, but the healthy settling of organic material.

What makes this behavior extraordinary is its self-regulating nature. Unlike Western papers that become brittle when dry or develop mold when damp, Xuan paper achieves equilibrium through its structure. The long, interlocking fibers create capillary channels that redistribute moisture at a microscopic level. A seventeenth-century manual for papermakers describes this as "the dragon's breath in winter sleep" - the material's capacity to maintain internal balance despite external extremes.

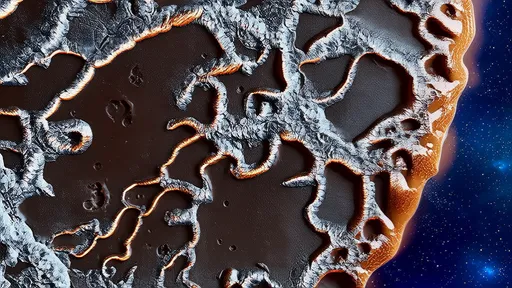

Recent studies at the National Library of China have captured time-lapse microscopic footage showing the paper's surface topography changing throughout daily humidity cycles. The fibers don't merely shrink uniformly; they adjust in coordinated waves, with areas under ink deposits moving differently from blank sections. This explains why classical Chinese calligraphy appears to "float" slightly above the paper surface after centuries - the inked fibers have stabilized while their untreated neighbors continue breathing.

The implications for preservation are profound. Western conservation methods often prioritize static stability, sealing artifacts in climate-controlled cases. But researchers now understand that depriving Xuan paper of its natural humidity variations causes more harm than good. Like a muscle that atrophies without use, the fibers' responsive capacity diminishes when denied seasonal cycles. The Beijing Cultural Heritage Institute has begun implementing "breathing periods" in their storage protocols, allowing controlled exposure to natural atmospheric rhythms.

This living quality poses fascinating questions about how we define material endurance. The oldest surviving Xuan paper documents, including several Tang Dynasty Buddhist sutras, have outlasted countless "more durable" materials precisely because they accommodate change rather than resist it. The paper's strength lies in its suppleness, its willingness to yield slightly to environmental pressures while maintaining structural integrity - a philosophy encoded in both its manufacture and the brushstrokes it carries.

Contemporary artists working with Xuan paper report that even new sheets exhibit this dynamic character. Modern calligrapher Lin Yao describes the sensation: "When working on autumnal mornings, I can feel the paper tightening beneath my brush like skin responding to cold. By midday, the surface relaxes, accepting the ink differently." This temporal dimension adds profound complexity to artistic practice, requiring masters to understand not just space but the fourth dimension in their compositions.

The paper's respiratory behavior also explains its legendary resistance to yellowing. The constant microscopic movement prevents the accumulation of static charges that attract dust and pollutants. Furthermore, the fiber adjustments distribute stress forces that would otherwise concentrate along fold lines or edges. Where machine-made papers fail along predictable stress points, Xuan paper's adaptive structure disperses tension throughout the sheet.

Perhaps most remarkably, this characteristic appears intentionally designed. Tenth-century records from Jing County papermakers describe a "seven-day awakening" process where finished sheets were exposed to carefully timed humidity variations before sale. Modern chromatography has detected subtle differences in fiber bonding between papers subjected to this traditional conditioning versus those immediately sealed. The ancients, it seems, understood the need to "train" the paper's responsive capacity.

As digital preservation becomes ubiquitous, the Xuan paper phenomenon offers a poignant counterpoint. Our contemporary obsession with perfect, unchanging replication stands in stark contrast to this ancient technology that finds longevity through graceful adaptation. The scrolls that have survived dynasties did so not by fighting time, but by moving with it - each barely perceptible breath of fiber against fiber writing another century into their story.

In museum basements and mountain temples where these papers reside, the Dry Concerto continues its endless performance. The next movement begins as morning humidity touches a Yuan Dynasty landscape painting, the fibers stretching awake to greet another day of their quiet, perpetual dance with the air.

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025