The world of Chinese calligraphy and ink painting holds many secrets in its brushstrokes, but perhaps none so fundamental - yet so poorly understood - as the mysterious dance between ink and raw xuan paper. Mo Yun Mao Xi: The Relativity of Ink Diffusion on Raw Xuan Paper explores this ancient alchemy where fluid meets fiber, creating what scholars have called "the heartbeat of Chinese art."

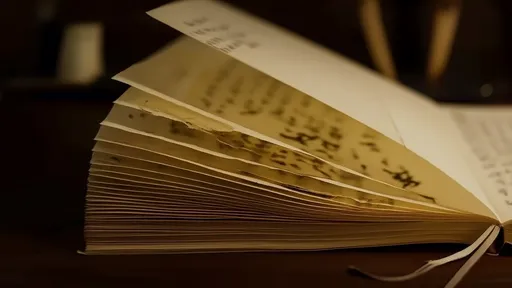

Walking into a master calligrapher's studio, the untrained eye might see only simple tools - ink stick, grinding stone, brushes, and stacks of unremarkable-looking paper. But to initiates, that humble sheng xuan paper represents one of humanity's most sophisticated cultural inventions. Its very name whispers of provenance; true xuan paper comes exclusively from Jing County in Anhui Province, where the Qingyi River's pure waters and local sandalwood trees have created perfect papermaking conditions for over 1,500 years.

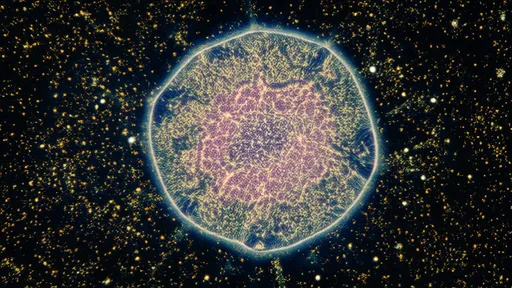

What makes raw xuan paper extraordinary isn't apparent until ink touches surface. Unlike sized papers that resist liquid, sheng xuan behaves like a thirsty landscape, absorbing ink along cellulose canyons with unpredictable yet somehow inevitable patterns. This isn't mere absorption - it's a conversation. The paper's long fibers, left unadulterated by alum or other sizing agents, create capillary channels that pull pigment particles in fractal migrations. Master painters speak of the paper "accepting" or "refusing" ink in ways that seem almost willful.

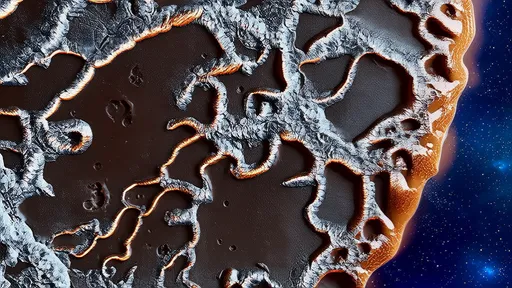

The physics behind this phenomenon reveals astonishing complexity. Under microscopes, raw xuan shows a three-tiered fiber structure unlike any other paper - coarse, medium and fine layers interwoven like mountain ranges seen from different altitudes. When ink hits the surface, these layers wick moisture at varying speeds, creating the characteristic "feathering" (run) effect prized by artists. But here's the marvel: the same paper will produce different diffusion patterns depending on ink viscosity, brush pressure, humidity, and even the artist's breathing rhythm.

Contemporary materials scientists have measured xuan paper's absorption rate at 38% faster than premium watercolor papers, with pigment particles traveling up to 2.3cm from initial contact points. Yet traditional masters need no measurements - they feel the paper's readiness in their fingertips. Old workshops teach apprentices to "listen" to paper by rustling sheets near their ears; the right harmonic resonance indicates proper fiber alignment for controlled diffusion.

This sensitivity to environment makes raw xuan paper notoriously difficult for beginners. A brushstroke that forms crisp lines in Beijing's dry winter might blossom into a ink puddle in Shanghai's humid summer. Great Ming Dynasty manuals describe micro-climate preparation techniques - steaming paper to precondition humidity, or exposing sheets to specific moonlight phases to "balance their qi." Modern artists use humidifiers and dehumidifiers to similar effect, though purists argue this loses something essential in the process.

The cultural implications run deep. Chinese aesthetics prizes the balance between control and spontaneity - what scholars call "controlled accident". In ink painting, the artist guides but doesn't wholly dictate the ink's journey. A bamboo stalk's outline might stay sharp where the brush paused, then dissolve into misty gradients where the ink continued wandering through paper fibers. This mirrors Daoist philosophies of harmonizing with natural forces rather than conquering them.

Conservation science has recently turned attention to xuan paper's unique aging properties. Properly stored raw xuan becomes more absorbent with time, as fibers continue relaxing into what curators call "mature readiness." The National Palace Museum's tests show 18th century xuan paper exhibiting 15-20% greater ink diffusion than modern equivalents, possibly due to centuries of microscopic fiber alignment changes. This presents both opportunities and challenges for restorers working on ancient masterpieces.

Modern artists push these boundaries further. Some soak xuan paper in herbal concoctions - chrysanthemum tea for golden undertones, or indigo baths for cool diffusion patterns. Others experiment with multi-layered applications, allowing ink to penetrate several sheets then peeling them apart to reveal fractal patterns. A Beijing-based collective even creates "ink performance" pieces where audience members blow on wet brushstrokes to collaboratively steer the ink's path.

The global art world has taken notice. At last year's Venice Biennale, Finnish artist Kaino Wenell presented "Xuan Conversations" - a installation where humidity sensors triggered ink dispensers onto raw xuan sheets, creating evolving maps of Venice's microclimates. Meanwhile, materials labs from MIT to Kyoto University race to decode xuan paper's molecular secrets, hoping to replicate its properties for applications ranging from medical diagnostics to water purification.

Yet for all this scientific attention, the essence remains mystical. As 96-year-old master Wang Xizhen observes while painting orchids in his Hangzhou studio: "The paper remembers every touch, every breath. When I'm gone, my ink will still be moving through these fibers, slower than eyes can see but faster than mountains erode. That's the true mo yun mao xi - not just ink's rhythm, but time's rhythm made visible."

Perhaps this explains raw xuan paper's enduring magic. In an age of digital perfection, it remains stubbornly, beautifully alive - responding to environment, revealing the artist's slightest hesitation, capturing not just images but the very movement of creation itself. The ink may fade over centuries, but the paper never forgets how it flowed.

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025