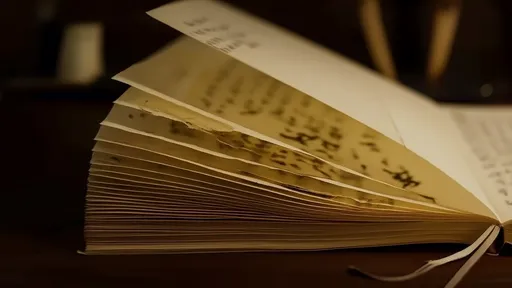

In the hushed elegance of a Song Dynasty tea room, where scholars and poets gathered, an ephemeral art form thrived—one that transformed the simple act of drinking tea into a meditation on impermanence. The practice of diancha, or whisked tea, was not merely a beverage preparation but a performative ritual that captured the essence of cosmic transience. The froth that crowned these meticulously prepared bowls was more than aesthetic; it was a microscopic universe, a fleeting galaxy of bubbles that mirrored the Taoist principles of change and the Buddhist acceptance of evanescence.

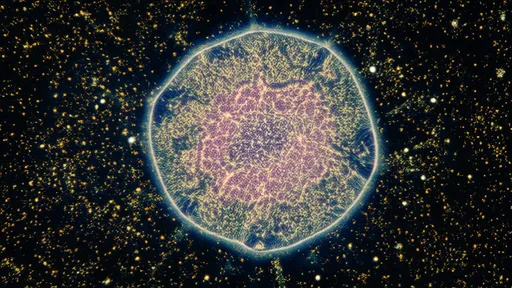

The preparation of whisked tea was an alchemical process. Tea leaves, finely ground into a vibrant green powder, were mixed with hot water and vigorously whisked with a bamboo chasen until a thick foam emerged. This foam, resembling jade-white clouds or mountain mist, was the heart of the ritual. Its lifespan was brief—sometimes lasting only as long as it took to appreciate its intricate patterns before it dissolved back into the liquid. To the Song Dynasty tea masters, this was no accident. The foam’s transient nature was a deliberate metaphor, a reminder of the “momentary brilliance” that defined existence itself.

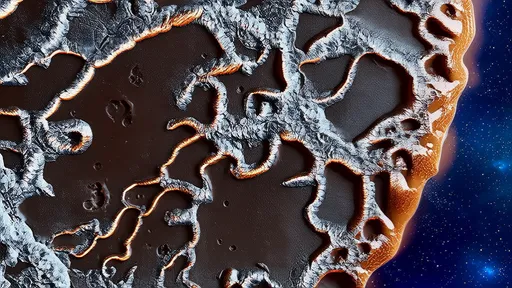

Modern scientists studying fluid dynamics might describe the foam’s behavior in terms of surface tension and bubble coalescence, but to the Song literati, it was a canvas for philosophical inquiry. The foam’s delicate structure—its shifting landscapes of bubbles forming and popping—echoed the I Ching’s teachings on cyclical change. Some tea practitioners even likened the foam’s collapse to the dissipation of human thought, a visual parallel to Zen mindfulness exercises. The act of observing the foam became a form of active meditation, where the drinker was invited to confront the beauty of dissolution.

The tools of diancha were designed to heighten this awareness. The tea bowls, often dark-glazed to contrast with the foam’s whiteness, acted as miniature stages for this cosmic drama. The chasen’s bristles, carefully split to precise thicknesses, created bubbles of varying sizes, each contributing to the foam’s texture. Even the water temperature was calibrated to perfection—too hot, and the foam would collapse prematurely; too cool, and it would never achieve its full, luminous height. Every variable was a variable in an equation of transience.

What makes the Song Dynasty’s obsession with tea foam particularly striking is its contrast with earlier Tang Dynasty tea customs, where tea was boiled with spices and consumed as a hearty brew. The Tang approach celebrated robustness and longevity, while the Song embraced fragility. This shift reflected broader cultural movements—the rise of Neo-Confucianism’s focus on “investigating things” (gewu), the influence of Chan Buddhism’s emphasis on present-moment awareness, and the growing prestige of scholar-officials who saw tea as a medium for intellectual discourse.

Today, as physicists explore quantum foam theories—the idea that space-time itself may be made of ephemeral bubbles at the smallest scales—the Song tea masters’ fascination takes on new resonance. Their intuitive grasp of foam as a model for universal principles feels almost prophetic. Contemporary tea practitioners attempting to recreate diancha often speak of the challenge not just in technique, but in cultivating the right mindset. To master whisked tea is to surrender to the fact that perfection, like the foam itself, cannot be held—only witnessed.

The legacy of diancha endures in Japan’s matcha tradition, but the original Song practice, with its explicit celebration of impermanence, remains distinct. Museums housing Song-era tea ware display bowls that once held these vanished microcosms, their glazes still whispering of the “ten thousand things” that arise and pass away. In an age obsessed with preservation and permanence, the Song Dynasty’s whisked tea ritual offers a counterpoint—an invitation to find profundity in what lasts no longer than a breath.

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025