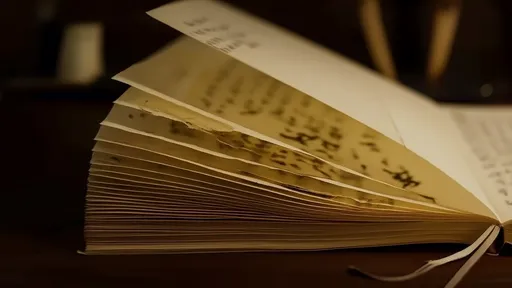

The ancient art of indigo fermentation is a dance between time, chemistry, and human intuition. In the quiet corners of dye workshops across Asia, vats of indigo undergo transformations that seem almost alchemical. The process, known as sukumo in Japanese or lan ran in Chinese, depends not on precise measurements but on the subtle cues of nature – particularly the moon's phases. This relationship between lunar cycles and dye fermentation has been passed down through generations, a whispered secret among master dyers who swear by its effects on color depth and fabric absorption.

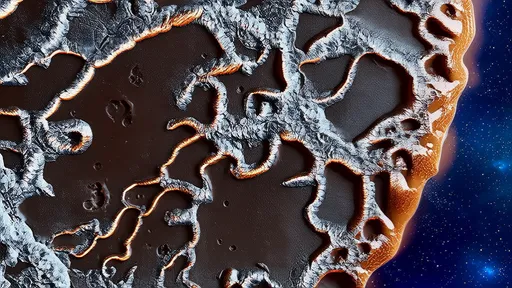

When the indigo leaves are harvested, they carry within them the potential for brilliant blues, but unlocking this requires patience. The leaves are dried, then submerged in water where they begin to ferment. Over weeks, sometimes months, the mixture transforms. The vat becomes a living entity, its surface developing a peculiar iridescent sheen that master dyers call "the flower." This bloom is actually a layer of aerobic bacteria working in symbiosis with anaerobic organisms beneath. The moon's gravitational pull, though subtle, affects this microbial activity in ways science is only beginning to understand.

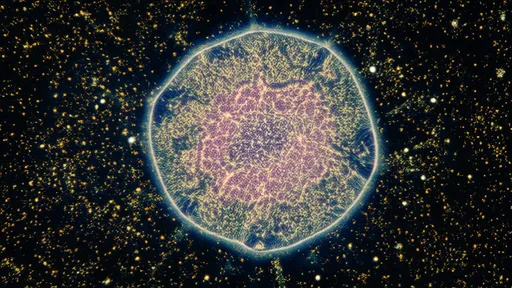

Traditional dyers time their work around the lunar calendar, believing that waxing moons produce more vibrant colors while waning moons yield subtler shades. Modern studies have found curious correlations – the bacterial colonies do show different metabolic rates during different moon phases, though whether this directly impacts dye quality remains debated. What's undeniable is that moon-phase fermented indigo develops a complexity that industrial processes cannot replicate. The blues seem to have more dimension, shifting between greenish undertones and deep violet hues depending on how the light catches them.

The fermentation vat becomes a microcosm of the natural world. As the indigo reduces, it passes through color stages that mirror twilight transitions – from greenish yellow to turquoise before settling into its famous blue. Master dyers judge readiness not by timers but by the way the liquid coats their fingers, by the particular scent it develops, even by how it sounds when stirred. This intuitive knowledge, accumulated over lifetimes, stands in stark contrast to modern dye factories where consistency is prized above all else.

Climate plays its part too. The same indigo leaves fermented in different regions produce distinct colors – the mineral content of local water, ambient temperatures, even altitude all leave their mark. Some workshops maintain their fermentation vats for decades, even centuries, with each new batch "seeded" from the previous one. These ancient vats are said to produce the richest colors, their microbial communities having adapted perfectly to their environment over generations.

In an age of instant gratification, indigo fermentation teaches the value of slowness. A batch might take three months to mature properly, during which it must be tended daily – stirred, tested, protected from temperature fluctuations. The dyer becomes attuned to the vat's needs much like a baker knows their sourdough starter. This intimate relationship between craftsman and material is perhaps why naturally fermented indigo commands such reverence. When cloth finally emerges from the vat, its initial greenish color oxidizing to blue before the dyer's eyes, it carries within it not just pigment but time itself.

The moon's role in this process remains partly mystical, partly scientific. Its phases affect Earth's magnetic field, which in turn influences microbial behavior. The same gravitational forces that move tides may subtly alter fermentation dynamics. Traditional dyers speak of "active" and "resting" periods in their vats that loosely correspond to lunar cycles. Whether this is observable science or generations of accumulated placebo effect matters little when the resulting colors speak for themselves.

Contemporary designers seeking authentic indigo now face a dilemma. While synthetic indigo offers consistency and speed, it lacks the living quality of vat-dyed fabric. Some have turned to small-scale artisans keeping the old methods alive, willing to pay premium prices for cloth that remembers the moon's rhythms. In Japan, certain kimono dyers still coordinate their work with the lunar calendar, producing limited batches of "moon-timed" indigo that sell out years in advance.

Perhaps the greatest magic of indigo fermentation lies in its imperfection. No two batches are identical, each carrying the unique signature of its making. The variations that would be rejected as flaws in industrial production become marks of authenticity here – slight irregularities that prove the human hand behind the process. In our homogenized world, such individuality has become precious. When you hold a piece of traditionally fermented indigo cloth, you're not just holding dyed fabric – you're holding a moment in time, a phase of the moon, a collaboration between human and microbe that will never repeat in quite the same way again.

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025