In the quiet corners of tea rooms and the hands of seasoned collectors, Yixing teapots whisper stories. These unassuming vessels, crafted from the famed purple clay of China’s Jiangsu province, are more than mere tools for brewing tea. They are repositories of memory, their surfaces etched with the passage of time and the devotion of their caretakers. The phenomenon known as "tea staining" or "nurturing the pot" (yang hu) transforms these teapots into living artifacts, their evolving patina a testament to years—sometimes generations—of ritualistic use.

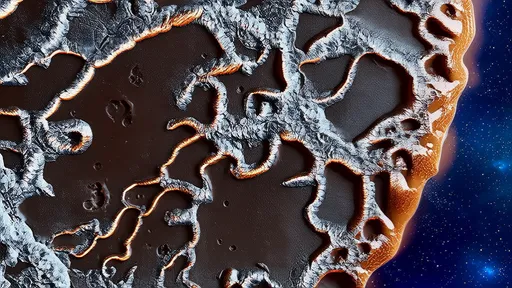

The allure of Yixing teapots lies in their porous clay, a unique mineral composition that absorbs the essence of tea over decades. Unlike glazed ceramics, these pots develop a lustrous sheen through repeated use, their colors deepening like the rings of an ancient tree. Connoisseurs speak of this process with reverence, comparing it to the cultivation of friendship or the slow maturation of a fine wine. Each stain, each subtle shift in hue, becomes a diary entry—a record of shared moments and solitary reflections.

This intimate relationship between object and user defies modern disposability. In an era of mass-produced goods, the Yixing tradition demands patience. A new pot must be "broken in" with a single tea variety for months before revealing its true character. The clay remembers: an oolong-drinker’s pot will eventually reject the sharper notes of green tea, its molecular structure imprinted with ancestral preferences. Such specificity borders on the mystical, as if the clay itself develops a palate.

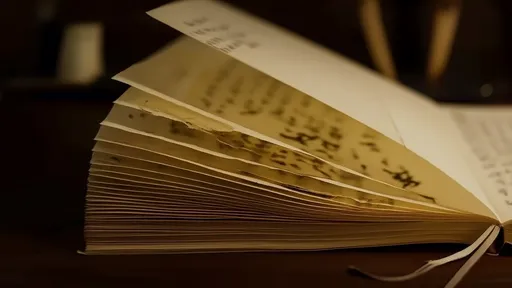

The cultural weight of these transformations extends beyond aesthetics. During China’s Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), when Yixing teapots rose to prominence, scholars elevated tea drinking to a philosophical pursuit. The gradual staining process mirrored Confucian ideals of self-cultivation—both required consistent effort and left invisible marks that shaped one’s essence. Today’s collectors often inherit pots bearing the stains of ancestors, the tea residues serving as a tangible connection to the past. One Shanghai-based collector described opening a century-old pot to find its interior "like looking into a forest at dusk—all those layers of darkness holding warmth."

Contemporary artisans continue this legacy while grappling with commercialization. Authentic Yixing clay, mined from diminishing reserves, now commands prices rivaling precious metals. Some workshops mass-produce pots with artificial stains to mimic decades of use, a practice purists deride as "forgery of time." Yet the true magic resists replication. As veteran potter Huang Wei explains: "You can fake the color, but not the quiet pride in a pot that’s been loved for thirty years. That kind of beauty has gravity."

The science behind tea staining reveals why shortcuts fail. Microscopic analysis shows tea oils bonding with clay particles at a crystalline level, creating permanent chemical changes. Heat from brewing expands the clay’s pores, allowing deeper infusion—a process that accelerates during the "opening up" ritual where new pots are steeped in discarded tea leaves. Over years, this builds a natural nonstick coating that enhances flavor. Japanese tea master Harada Yasuko notes: "Western cooks season cast iron; we season clay. Both are acts of faith in materials that outlive us."

Perhaps the most poignant aspect lies in the pots’ imperfections. Unlike factory-perfect ceramics, hand-built Yixing teapots bear slight asymmetries—finger grooves from their makers, tool marks that catch light differently as stains accumulate. These "flaws" become focal points for meditation, much like the deliberate irregularities in wabi-sabi aesthetics. Collectors often speak of recognizing their pots by touch in darkened rooms, the topography of stains serving as braille-like love letters from the past.

In Taiwan’s tea circles, a tradition called "pot adoption" has emerged, where elderly enthusiasts bequeath their stained teapots to younger custodians. The transfer involves elaborate ceremonies, including brewing sessions where the new owner learns the pot’s "rhythm." Such practices underscore how Yixing teapots transcend ownership to become kinship objects. As tea seller Lin Xiaofeng observes: "Nobody truly owns these pots. We’re just caretakers between generations, adding our chapter to their story."

The stained Yixing teapot endures as an antidote to digital ephemerality. In a world of disposable pixels, it offers tactile permanence—a vessel where time doesn’t vanish but accumulates visibly, sip by sip. Each stain is a protest against forgetting, a promise that some things grow more valuable with use. As sunlight filters through a well-loved pot’s translucent patina, it illuminates what our hurried lives often overlook: that depth comes not from newness, but from the courageous act of staying present, season after season.

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025