In the dimly lit archives of forgotten sound, a peculiar revolution lies encased in fragile shells of beeswax and cardboard. The Victorian phonograph cylinder—often overshadowed by its disc-shaped successors—holds within its spiral grooves an entire anthropology of human experience. These whispering wax tubes are not mere relics of early audio technology but rather biographic vessels, each carrying the intimate pulse of a moment frozen in amber.

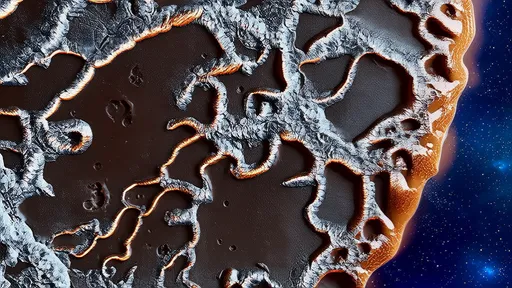

The very materiality of these cylinders betrays their organic nature. Composed of beeswax, paraffin, and later metallic soaps, they quite literally embody the cultural hive from which they emerged. Unlike the sterile perfection of digital recordings, these artifacts bear the scars of their survival—mold blooms in their grooves like lichen on ancient stone, while hairline fractures trace across their surfaces like cartographies of lived experience. To hold one is to cradle a fossilized vibration, a captured breath from an era when sound itself was still a novelty.

What makes these cylinders particularly extraordinary is their accidental humanity. The limitations of early recording technology demanded that performers press their lips nearly against the horn, resulting in audio that still carries the wet click of saliva, the rasp of a pre-performance throat clearing, even the suppressed laughter of musicians startled by their own disembodied voices. These were not the polished productions of later eras, but sonic snapshots where the boundaries between performance and private moment dissolved entirely.

The content preserved on these wax cylinders forms a mosaic of Victorian consciousness. Alongside expected musical performances exist far more revealing artifacts—the trembling voice of an elderly veteran recounting the Battle of Waterloo decades prior, the singsong rhymes of nannies recorded without their knowledge, even the clandestine whispers of lovers who rented recording equipment as novelty entertainment. Unlike the carefully curated paper archives of the period, these accidental documents preserve the grain and texture of lived experience in a way no written record ever could.

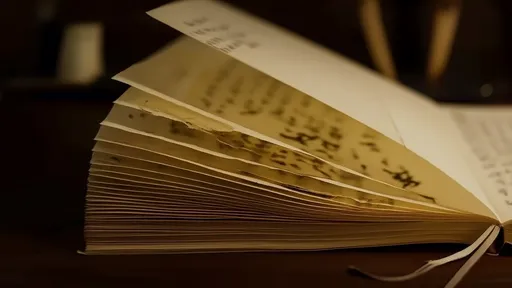

Modern archaeology of sound has revealed even more startling dimensions. Advanced imaging techniques applied to severely degraded cylinders have uncovered "ghost recordings"—layers of earlier performances that were shaved away for reuse but left faint impressions in the wax. Like palimpsests, these cylinders often contain multiple temporalities superimposed upon one another: a bawdy music hall song might conceal beneath it a child's recitation, or a businessman's dictation might mask a domestic quarrel accidentally captured when the recorder was left running.

The ethical dimensions of listening to these recordings today provoke uncomfortable questions. Many contain voices of individuals who never imagined their utterances might outlive them by centuries, let alone be subjected to digital analysis. There's something profoundly intimate about hearing a Victorian woman's private singing practice, complete with her frustrated pauses and self-corrections. These were sounds meant to evaporate into the air, not to be preserved under glass in perpetuity.

Perhaps most haunting are the unidentified recordings—the laughing children, the snippets of forgotten languages, the solitary whistlers—whose contexts are lost to time. These orphaned sounds float through the digital archives of modern institutions, severed from their original meanings yet still vibrating with human presence. They remind us that every technological medium, no matter how obsolete, carries within it the indelible imprint of those who used it to say: I was here.

As contemporary researchers develop methods to extract ever more information from these delicate wax cylinders—analyzing the dust trapped in their grooves for environmental data, studying the wear patterns to reconstruct playback histories—we must remember that we're not merely recovering sound. We're exhuming entire ecosystems of human interaction, fragile as the medium that preserves them. Each cylinder is a séance conducted in the language of physics, where the dead speak not through spiritualist tricks but through the very real vibrations they left behind in soft wax over a century ago.

The story of Victorian recording technology is typically told as one of mechanical triumph. But the wax cylinders ask us to reconsider this narrative—not as a chronicle of devices, but as the earliest chapters of humanity's attempts to conquer mortality through captured sound. In their fragility, in their imperfections, and in their stubborn refusal to be completely decoded, these waxen time capsules remain profoundly, uncomfortably alive.

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025